NEW VRINDABAN DAYS – CHAPTER 9

NEW VRINDABAN DAYS

As New Vrindaban celebrates its 50th anniversary (1968 to 2018), I wrote this series of articles for the Brijabasi Spirit in an attempt to give the reader not only an “understanding,” but more importantly a “taste,” of what life in early New Vrindaban was like – through the stories of one devotee’s personal journey.

The title of the series, “New Vrindaban Days,” is in tribute to the wonderful book “Vrindaban Days: Memories of an Indian Holy Town” written by Howard Wheeler, Hayagriva Dasa. He was one of Srila Prabhupada’s first disciples, a co-founder of New Vrindaban, and, a great writer. As with Hayagriva’s book, this series focuses on a period of time in the 1970’s.

I would also like to acknowledge and thank Chaitanya Mangala Dasa, for spending untold hours assisting me in refining my writing for your reading pleasure.

I have been asked to describe certain aspects of early New Vrindaban Community life such as the nature of the austerities, what it was like for a new person coming here, cooking, anecdotes about particular devotees, etc.

I attempt to tell these stories in some semblance of a chronological order, beginning with my first meeting with devotees in 1968, leading to my arrival in New Vrindaban in late 1973 and carrying through to the official opening of Srila Prabhupada’s Palace in 1979.

This article describes some of my experiences from 1974, the first year I lived in New Vrindaban.

Advaitacharya Dasa

CHAPTER NINE: The Death of the Vedic Civilization

I was initially slated to work the horses temporarily, but it has become increasingly obvious I will not be going back to my former service in the woodshed.

There are three teams of horses in the Bahulaban horse barn with the best of them being the beautiful young Belgian team of Tom and John. They are young, smart, and strong and worked regularly by Kasyapa. Next are the older team of white horses named Prince and Molly, behind which Romaharsana has generally held the reins. Things in the barn are kept interesting by the fact that Prince is not a gelding. For those not familiar with equine jargon this means that Prince is still fully equipped as a stud horse for breeding. When removing Prince from his stall you must be sure not to let him have a clear view of the back side of Molly’s…stall. If a mistake is made, Prince goes crazy.

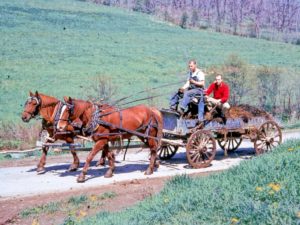

As a new driver I am being trained on a younger and less efficient team named Ranchor and Saibya. Ranchor is dark brown, while Saibya is a lighter, reddish color. The Bahulaban horse barn is a simple shed covered with corrugated steel containing four stalls. It is located across the state road across from the Bahulaban temple, north east about fifty yards.

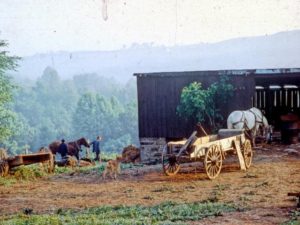

The designated horse drivers, Kasyapa and I, are in the barn early in the morning seven days a week cleaning the stalls, giving the horses fresh hay and grain, marching them one at a time through the mud for a drink at the creek, brushing and cleaning them, and then putting them into their harnesses. Scattered around the small meadow the barn is located on, are various pieces of vintage horse drawn farming equipment: an old blue box wagon, a low to the ground wood sled, a large flatbed hay wagon, a rusty dung covered manure spreader, etc.

On one side of the barn is the tack room where the harnesses, bridles, and other equipment are kept and repaired when necessary. I have to quickly learn all kinds of implements that I am completely unfamiliar with. What is a singletree? What is a doubletree? What is the difference between a cultivator and a plow? What is a bridle, a bit, and a curry brush? This Brooklyn boy is being countrified.

Driving the horses allows me to come in contact with all the different aspects of the community. Everybody, every department, and every one of the four farms has something for the horses to do. There are no vehicles to do any heavy moving. Everything is done with the horses. I bring wood to the woodshed, manure to the gardens, haul away trash to different dump sites, transport young apple trees to be planted with Bhakta Mark (soon to be Madhava Ghosh), and even empty the outhouses.

I will save the description of this activity for another article. One may ask, why would a description of emptying the outhouse might deserve placement in another article? I will only say that the issue of “sewage” in the primitive setting of New Vrindaban, housing over 100 people with no proper sanitation system, was, for many “board meetings,” the number one topic of discussion.

Speaking of dung, the cowherd boys are milking 16 cows twice a day in the original barn of the Coffield farm that is now Bahulaban and the amount of cow dung produced daily is daunting. It is practically impossible to spread the manure on the fields in the winter using the horse drawn spreader so the entire task is done by hand. The barn sits up the hill approximately 30 or 40 feet above the state road. On the road side of the barn there is a 3 ft. x 3 ft. open doorway out of which the cowherd boys shovel dung directly down onto the hillside. The dung pile is so large that the cowherd boys and the horse boys affectionately refer to it as “Govardung Hill.”

In order to get the horses close enough to the hill to remove any of the dung, I must bring the horses and wagon through a huge puddle of mud and then down a short, steep access road and bring the team to a sharp stop on the hill standing almost knee deep in mud. When the horses are able to come to a stop I, along with whatever other new bhakta has been assigned to work with me, must jump off into the dung hill with pitchforks to fill the wagon.

Anyone familiar with the nature of keeping barn animals knows that when we talk of cleaning cow dung out of stalls we are talking not only of pure dung but a dense mixture of dung and straw the cows sleep on. As “Govardung hill” settles in for the winter, the mixture becomes compressed, moldy, and starts decomposing. It must be dug out with pitchforks in layers as if peeling a huge, black, onion. After the wagon has been filled with a ton or so, the two of us must take it to a field somewhere and use the pitchforks to toss it off of the wagon while the horses continue to walk slowly along. All this in the dead of winter.

As new bhaktas arrive they are often assigned to work with me for a couple of days, giving me an opportunity to form what will become lifelong friendships with devotees like Bhakta Carlos (Nityodita Das), Bhakta Terry (Tapahpunja Das), Bhakta Mike (Manonatha Das), Bhakta Tony (Tejomaya Das), Bhakta Kevin (Kholavecha Sridhara Das), Bhakta Kurt (Sarvasaksi Das), and many others.

In addition, I get the rare opportunity to engage in what might only be referred to as special and unique. Since the original Vrindaban farm is inaccessible by motorized vehicle, I must take all supplies that are needed for survival every week or two. In the middle of the day I arrive to find the only brahmacari who spends his day in this isolated homestead. He is the caretaker of the Deities Sri Sri Radha Vrindaban Nath, Radhanath Das (later to become Radhanath Swami). He is thrilled to have someone different visiting the farm and we sit together taking lunch prasadam and exchanging stories. The visit often culminates in the two of us sitting together singing bhajans which echo through the hills and trees. Another lifelong friendship ensues.

On one visit to the Vrindaban farm, I have unusual cargo. Radhanath’s father has come to visit from Chicago. There is no other way for him to get to Vrindaban, so I am charged with taking him there. It is still winter and we get there using the old blue wagon, which is coated with a thick layer of frozen, crusty cow manure. We find an old blanket to cover him with and share a crowded seat on a bale of hay over the three mile bumpy road.

When we arrive he is stunned to see the simple and austere conditions his son is living in. It doesn’t seem that it can get any worse until he asks Radhanath where the rest room facilities are. When Radhanath explains the devotees take a shovel out to the nearby woods his father decides he will hold it in.

When his father is ready to depart, after only a brief encounter with his son, he asks Radhanath if there is anything he needs. When Radhanath explains he has everything he needs, his father breaks down and begins to cry. Being an eyewitness to the extreme deprivation Radhanath is living in, his father is still crying as he boards our shared hay bale. We sit silently together for the somber ride down through the stark, winter woods.

For a time the women’s ashram is moved to Madhuban and I am charged with transporting the ladies up and down the road in a recently purchased stagecoach. Kirtanananda Swami has been making his trips on Sunday night to the Vrindaban brahmacari farm in the manure wagon until we purchase an Amish buggy and I begin taking him up the road in style.

The highlight of my horse driving career comes when Srila Prabhupada visits New Vrindaban in July of 1974 and I contrive a plan so that I will stand out and be recognized by him.

His Divine Grace is staying up the road in a recently purchased house in an area called “Guruban,” near his Palace construction site. Each day he must be picked up in a vehicle and brought to Bahulaban so he can give the morning lecture. While all the devotees are wearing their temple clothes waiting to greet him I instead, don my work clothes and proceed to the horse barn.

The day before I stacked the flat bed wagon four layers high with bales of hay. The entire load amounted to the size of a 24 foot box truck. Although there is no call to bring hay anywhere, my idea is I would be atop the load, driving the wagon and the two steeds right toward Srila Prabhupada’s car as he approaches Bahulaban.

My hope is he would surely see me like a charioteer from the battlefield of Kurukshetra, standing high, holding the reigns, muscles tightly flexed, controlling the two large horses. In that way, he would recognize me as one of New Vrindaban’s hardest working devotees.

I harness the horses and drive the load onto the road and head directly for where I know Srila Prabhupada would soon be coming. After traveling no more than 500 yards the car carrying Srila Prabhupada comes into view and is headed right at me. I stand tall, imagining my sikha blowing in the wind, and my tilak glowing in the morning sun. As the car passes below me I lower my eyes to look directly at Srila Prabhupada, who is gazing up at me through the side window of his car. Success!

After he passed, I turn the wagon around and bring it back to the barn. I unhook the horses, run to the temple, don my temple garb, and attended the lecture. No one being the wiser.

When the lecture ended Srila Prabhupada is driven back to his quarters by Kirtanananda Swami and I proceed to the Swami’s cabin to wait to hear any other pastimes that might have occurred with Prabhupada at his house.

Srila Prabhupada at Bahulaban, getting into the car that will take him to the Grey House at Guruban, 1974.

I took a seat against the wall across from the Swami’s desk and chatted with the other devotees until he arrived, about an hour later. The Swami sat on the floor behind his desk answering questions about whatever had transpired with Srila Prabhupada. After about a half hour he suddenly recalled something and addressed me directly.

“Bhakta Emil, Srila Prabhupada saw you driving the horse wagon up the road!”

I responded incredulously, acting as if I hardly knew what he was talking about, while in reality I was hanging on every word, waiting for the praise I am 100% sure is coming.

“He did?” I peeped.

“Yes. When he saw you he said, ’This is the death of Vedic civilization.’“

As my heart sank, all eyes turned to me.

“The death of Vedic civilization?” I asked feebly.

“Yes, he said using horses and tractors means the oxen are not being engaged and therefore wouldn’t be protected. Vedic civilization depends on protecting the cows.”

My scheme had resulted not in Prabhupada recognizing me as one of Krishna’s best devotees. Instead, his seeing my activities prompted him to mention me in the same breath as the death of the Vedic civilization.

Oh well, I guess it could have been worse. At least he didn’t refer to me in the same sentence describing what it meant to be a sahajiya.

At least not this time…

—————————————————————————————-

Chapter 1: Every Journey Begins With a Single Step

Chapter 2: Srila Prabhupada – Jaya Radha Madhava

Chapter 3: Captured by the Beauty of Sri Sri Radha Vrindaban Chandra

Chapter 4: Fired Up – We Depend On Sri Sri Radha Vrindaban Chandra

Chapter 5: The New Vrindaban Landscape – January 1974

Stay tuned for Chapter 10: The Pits

The next monthly installment will be posted January 2019!